By Michael Knodt for marijuana.com

Eleven years ago, I was confronted with the phenomenon of contaminated cannabis for the first time.

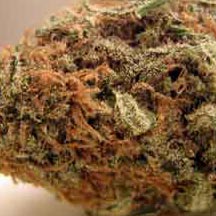

One of my colleagues had bought two grams from his private source and wanted to medicate in our editorial office. The medicine smelled and looked good, but visibly, despite the correct weight of 2.0 grams, it looked as if it was at least a half-gram short. When the bud was rubbed between the fingers, it felt rough, and licking the fingers after, something crunched between my teeth. Also, the hard-as-stone crystals sank to the bottom of the zipper-bag. Eventually I assumed the colleague had bought at least half a gram of fine sand. We decided to burn the sanded weed with a Jet-Stream lighter to see if there was any inorganic material left over. After burning the two grams, we had a dark green glass globe weighing about 0.5 grams. The sand used for diluting the bud had been fused into glass.

Startled by this incident, I looked online to see whether or not any other smokers have had similar experiences. At first, I only found reports in British forums where users blamed a substance called “Brix+” for the improper buds. This liquid substance should be blended with the flowers after drying as a “wet cure application”, so the producer stated on the bottle, that they weigh up to 22% more. After we did some brief research in German grow shops, it was clear that Brix had only been offered for a few weeks – it was advertised as a new yield enhancer from Australia. The soaked flowers actually weigh almost a quarter gram more, have lost almost all of their aroma, but appear extremely crystalline after the treatment.

White widow contaminated with sand

Everything Began With Brix

Brix is a unit of measurement normally used in wine growing that provides information on the sugar content, similar to Oechsle-Grading. Some fertiliser manufacturers from overseas, particularly in the UK, have taken over this fact, and they praise products that make bud particularly “heavy and sweet”, often in connection with the name Brix.

Once again, some criminals from the cannabis scene took advantage of this by placing the “Brix+” on the market and massively advertising it as a brand new yield enhancer. Our team searched and found somebody to test a sample in a mass spectrometer that had been sent to our editorial office anonymously. The liquid product contained a colorless plastic polymer.

Not too long after the first reports of “Brix+” contaminated cannabis appeared, the product was taken off the shelves of almost all grow shops across Europe. But anyone who thought the problem was solved at that time was not aware of the mechanisms of an uncontrolled black market. After Brix+ was taken from the shelves there was less and less uncontaminated cannabis on the black market, particularly in the imported buds from the Netherlands which became infamous for being dirty. No matter whether talcum, salts, sugar, oregano, fibre hemp, broken glass, or hairspray, dealers were padding their wallets with contaminants.

The public did not take notice of the phenomenon until 2008, when two people nearly died from contaminated cannabis. At that time, an unscrupulous dealer had the idea of using lead sulfide as a cutting agent. It shines beautifully, weighs a lot and very quickly causes lead-poisoning when smoked. After almost two hundred reported lead poisonings in and around Leipzig, the Federal Criminal Police Office (BKA) decided to test more seized samples.

Lead was no longer found, but a wide range of previously mentioned substances which definitely have nothing to do with cannabis were detected. However, testing cannabis from the black market is generally unlawful and, therefore, consumers have little chance of detecting cutting agents on their buds. If contaminated heroin or cocaine is seized there are public warnings to protect consumers. In the case of contaminated cannabis, potential consumers are not informed; politicians withdraw on the position that any consumption of cannabis is harmful and should be avoided. The only information available is on Cutting Agent Register pages like the Streckmittelmelder.

The register is still being filled with new content every day. Here, the often helpless consumers can learn how to use a few simple tricks to detect contaminations. An incomplete burning, sparks or a float-test of a bud in a glass of water can give hints on cutting agent contamination. But it cannot prevent health hazards caused by black market cannabis or create any consumer protections like in Oregon, Washington, or Colorado. In the south of Germany, where the penalties and profits for cannabis are the highest in the country, most incidents and probable contaminations are reported.

Back to the Roots

The only good thing about the phenomenon was the reflection of many consumers on their own abilities as home gardeners. The sales of the grow shops have increased since then proportionally to the amounts of cutting agents. Due to the popularity of home growing, the situation improved in Germany. However, this dangerous way of raising profits has even penetrated Amsterdam’s coffeeshop scene.

“Banana-Haze” or “Strawberry-Kush” often turns out to be the nastiest fruit-flavoured medicine. The buds are inedible, and start to mould in the zipper-bag after three hours, just like lettuce in a plastic bag. The cannabis college has warned its visitors not to purchase fruity strains since 2015, and even forbids its consumption in the college’s vaporiser with warning signs: “Please let the staff check your cannabis before using the vaporisers. Apple and Strawberry Weed are not allowed.” The warning in Amsterdam’s activist centre is the best evidence that the disgusting buds have reached the coffeeshops of Europe’s cannabis metropolis. During my last visit in 2016, the college’s staff informed visitors why the diluted buds destroy the expensive vaporiser. But despite the tireless explanation the Dutch activists, the next day I met a group of Canadians who had just purchased one gram of “Vanilla-Kush” for 17 Euro. The strain was procured from an established coffeeshop in Haarlemstreet; it smelled of cheap vanilla, was half wet and obviously impure. Despite my advice to return to the coffee shop to confront the budtender with his dangerous product and get their money back, they preferred to smoke it. At least the coffeeshop High Times, where I purchased my first and only contaminated sample of Banana Haze back in 2015, has since closed its doors.

Photos courtesy of DHV (German Hemp Association)

This article was originally published on marijuana.com. Read the original article.