Sex, drugs and rock’n’roll, amirite? Drugs and the music industry have long been associated with one another – both in legend and reality. But what about in Australia, right now? Writer Joseph Earp looks at drugs and the Aussie music industry today in this series done in collaboration with the BRAG. Read the second instalment of the series on Dopamine tomorrow, or pick up a BRAG magazine and read the whole thing in print.

“Man what’s the matter with that cat there? / Must be full of reefer!” – Cab Calloway, ‘Reefer Man’

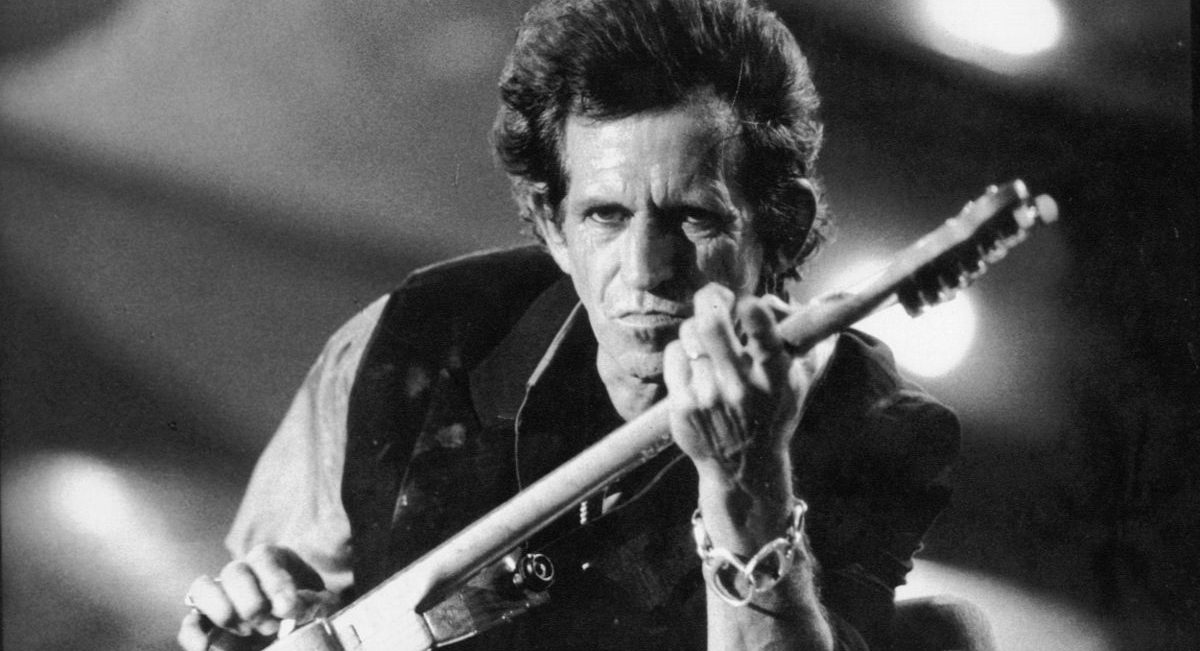

There are certain images that have become seared onto the pop culture consciousness. Images of tortured musicians slumped over their guitars, needles sticking out from their track-mark-studded arms. Of great rock’n’roll doyens hoovering up blow in a jacuzzi. Of performers searching for a quick pick-me-up before they head out under the bright lights of the stage. These are images that we now know intimately, that belong almost entirely to the realm of cliché.

After all, drugs and rock’n’roll are so deeply intertwined with one another that we often talk about both when only specifically mentioning one. They mean the same things to us. They mean excess, privilege, self-destruction and wealth. They mean all the things that we don’t often admit to ourselves we want, and all the things that we know might ultimately kill us.

Many of rock’n’roll’s most mythic, legendary tales concern the imbibing of titanic amounts of illicit substances. We are obsessed with these stories; we tell them to ourselves over and over across different mediums. They’re stories about musicians succumbing to the allure of drugs and then slowly, defiantly rising back up to the top.

Indeed, we like our heroes to come pretty fucked up. That’s why we are obsessed with the chemical fortitude of Motörhead’s Lemmy, a man who once claimed years of abuse had turned his blood into a treacly, narcotic-laced sludge. That’s why we love The Beatles’ experimental years, that short period where the once fresh-faced Fab Four transformed into a semi-mystic troupe of Jodorowsky-esque astral pioneers. And that’s why we love the punky detachment of Lou Reed, that arch junkie whose work was so often composed to be enjoyed with the help of hallucinogens.

This isn’t a contemporary endemic either, or one that began with the boomers. Lemmy, Reed and The Beatles might be the first to come to mind when we think of coked-up creatives, and yet they are but children compared to the performers of the ’30s and ’40s – the whacked-out weirdos who regularly pumped themselves full of illicit substances.

“Drugs have long provided popular music with one of its more ambivalent subjects,” writer Andy Gill noted in an article for The Independent. “The image of the jolly ‘reeferman’ is a recurring figure in jazz lore, and Ella Fitzgerald’s jocular ‘Wacky Dust’ [testifies] to the properties of cocaine.”

As far back as 1938, hysterical muckrackers like Radio Stars journalist Jack Hanley were writing articles topped with fearmongering headlines such as ‘Exposing The Marijuana Drug Evil In Swing Bands’.

“One leader told me of a young man in his band who was a crackerjack musician, but who used the weed so consistently that he was quite undependable,” wrote Hanley, the moral outrage shimmering just beneath the surface of his words. “The fits of deep depression reefers so often produce would seize him until he had to be restrained from suicide.”

That’s not even to mention the fact a host of songs now considered rock’n’roll standards were initially written as paeans dedicated to the losing of one’s mind. Songs about pot defined the ’30s (the decade that immensely popular performer Stuff Smith released the weed smoke-smothered ‘If You’re A Viper’), and the ’40s weren’t much cleaner – think boppy, seemingly bright and family-friendly tunes bursting with references to getting high and getting down.

Even ‘La Cucaracha’, that most seemingly innocent of songs (you know the one: that gleeful, leery tune we associate equally with sports chants and with Mexico) is actually about pot-smoking. “‘La Cucaracha’ crackled with life, a swaying Spanish-tune-turned-Mexican corrido quickly picked up by jazz bands and danced into popular music,” writes Margaret Moser in ‘If You’re A Viper’, her brilliant article penned for The Austin Chronicle about the history of drugs in music.

“No song better evoked the languorous image of life south of the border in vintage films, newsreels, and radio programs of the day. Yet few people realised the lyrics bespoke a cockroach’s yearning to stay high: ‘La cucaracha ya no puede caminar … por que no tiene marihuana por fumar,’ basically translates as, ‘The cockroach can no longer walk because he doesn’t have any marijuana to smoke.’”

By the time the ’50s and ’60s rolled around and the American counterculture movement strengthened and solidified, the theme of drug use took hold over pop music and rock’n’roll. Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On set the tone for all pot-laced pop epics that followed it; Charlie Parker’s An Evening At Home With Charlie Parker Sextet was a scatty, frenetic ode to heroin use; and Frankie Lymon’s The Teenagers Featuring Frankie Lymon was indebted to the drugs that would eventually claim Lymon’s life.

And from then till now, drugs and music have only become further entrenched in one another. They have only grown closer; each more indebted to the other as the years roll on.

“I think in many ways, it seems more odd now to encounter a band that doesn’t have at least one mention of drugs than it does to encounter a band that has lots of references to drugs,” one anonymous writer tells me. “It’s almost what we expect from music now.”

So, one has to ask: what has all that drug talk done to the popular consciousness? The question, for the record, is not designed to be framed in a puritanical way. It’s not a question about whether or not songs concerned with drugs have turned our children to the devil, fried their brains, or corrupted them and their youth. It’s more a question about whether or not we can even talk about drugs in music effectively in 2017. When you can no longer separate myth, lies, fiction and reality, can you say anything with any real authority?

At this stage, given all the stories that we have told ourselves, is it possible that we have lost sight of reality, confused by larger-than-life figures and their drug habits? Have the grand characters of rock’n’roll’s history become overly mythologised, now as true to life as the characters in children’s fairy tales? And, perhaps most pressingly of all – do we even know how to talk about drugs in the music industry any more?